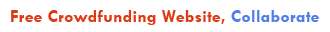

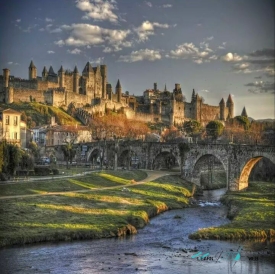

The Cité de Carcassonne is a fortified medieval city located on a hill in the old town of Carcassonne, in the Occitanie region of southern France. It is located on the right bank of the Aude and in the southeast of the current city. Its origins date back to Gallo-Roman times and it was enlarged into a fortress in the Middle Ages. The fortified city is surrounded by a double wall (each about three kilometers long with a total of 52 towers). The main buildings within the Cité, which is still inhabited, are a castle (Château comtal) and a church (Basilique Saint-Nazaire).

In the 19th century, the already decaying city of Carcassonne was restored under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. This resulted in an extensive well-preserved historical monument that was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Carcassonne was founded as Carcasso in the 1st century BC. Founded by the Romans on the site of today's Cité. The so-called Gallo-Roman towers with a horseshoe plan on the inner wall testify to the Carcasso period.

On the 14 hectares, where between 3,000 and 4,000 people lived in the Middle Ages, 229 permanent residents live today. All the others work for tourism and live abroad. La Cité is a large open-air museum used by tourists and is not normally accessible by car.

Legend has it that the fortress was once besieged by Charlemagne, when Mme Carcas was the lady of the castle. The siege lasted so long that famine soon claimed the first victims in the Cité. Mrs. Carcas then decided to stuff a pig with wheat and, when she was fat enough, she threw it off the castle wall. The besiegers, already exhausted, thought when they saw the fat animal that fell from their towers that the city must have food to spare. Dejected, Charlemagne's men gave up and returned home. When the town bells rang to celebrate the end of the siege, one of the besiegers is said to have exclaimed Madame Carcas sonne (Carcas sounds).

In 1208, Pope Innocent III, faced with the increase and extension of Catharism, decreed the Albigensian Crusade. The Count of Tolosa and the Viscount of Carcassonne are accused of heresy and their territories become the main target of the attack by the barons from France. On August 1, 1209, the city is besieged by the Crusaders. Raymond Roger Trencavel surrenders to them on August 15 in exchange for the lives of its inhabitants. The villages around the city are destroyed. The viscount dies of dysentery in his castle prison on November 10, 1209. Other sources speak of an assassination planned by Simon de Montfort.

The city becomes the headquarters of the crusade troops. The land and city are delivered to Simón de Montfort, military chief of the Crusader army. He died in 1218 during the siege of Toulouse and his son, Amaury VI de Montfort, took possession of the city, but was unable to manage it. He cedes the rights to it to Louis VIII of France, but Ramon VII of Toulouse and the counts of Foix allied against the king. In 1224, Ramón Trencavel II took possession of the city after Amaury fled.

Louis VIII launches a second crusade in 1226 and Ramón Trencavel must flee. The city of Carcassonne becomes part of the domain of the King of France and becomes the seat of a seneschal. A period of terror is installed inside the city among the inhabitants; the search and hunting of the Cathars multiplies the bonfires in the squares and there are continuous savage denunciations, with the installation of an Inquisition Tribunal within the city precincts.

Louis IX of France orders the construction of the second walled enclosure so that the city can withstand long sieges and sieges. Trencavel, refugee in Aragon, intends to recover his land. At the same time, the king of Aragon, Jaime I the Conqueror, is considered a constant threat to the region, very close to the borders of his kingdom, the city being part of the defensive system of the border between France and Aragon.

After the annexation of Roussillon to France by the Treaty of the Pyrenees, the military role of Carcassonne was greatly reduced, as the distance to the Spanish border increased considerably. The role of command post for the defense of the border was transferred to Perpignan.

The walls of the Cité date from various periods of construction. The oldest parts of the wall were erected at the time of the Visigoths. They can be recognized by the layers of small cube-shaped stones, interrupted by layers of bricks, and by the narrowness of the towers, which are already equipped with real windows. The castle was mainly built in the 12th century. The outer ring of walls with their smooth ashlars dates from the middle of the 13th century.

At the end of the 13th century some of the towers and parts of the inner wall were built, which was then being rebuilt and advanced. The ashlars from this period are mostly carved with art. The towers have several floors and are provided with loopholes. The building material for the two concentric belts of fortifications was brought from the surrounding quarries: hard sandstone, difficult to extract and work, but which over the centuries began to erode under the influence of violent storms from the southwest.

The interior of the walls is made of rounded stones, fragments of rock and sand, agglutinated with lime, which also serves as mortar. The texture of the masonry varies with each period of construction.

The regular outer wall, 1.5 kilometers long, was built in 15 years shortly after 1230, hence its uniform appearance. The construction history of the 1.3 km long inner wall is much more complicated and its masonry is far from uniform. At that time, the city already had a wall from the Gallo-Roman era that was around 1,000 years old, but it was no longer up to date. Today it forms the skeleton of the inner belt and can often be seen at the bottom of today's wall.

As always in such cases, the area between the two walls is called the Zwinger. The kennel kept the attacker in an area that militia projectiles could reach. The wall must be as high as possible, because until the 14th century people did not shoot back, they shot back. In times of peace, such a kennel was used for games and knightly combat festivals. In some cases, the old parts of the wall were supported on new foundations when they were tapped, so that the strange picture arises that the oldest part is higher than the later one.

The ditch around the wall was not filled with water, but it had the function of preventing the use of larger siege engines, which had to be directed against the wall at right angles to the direction of the Zwinger and therefore did not have sufficient access. here. The fortification of the city with a double fence corresponded to a new defensive tactic that had been designed around 1200 around the king in the time of Philip Augustus (1180-1223). His principle was: the defense must be active, it must be able to inflict heavy losses on the attacker. Therefore, more than a thousand archers were stationed on the battlements, and the towers flanked the entire wall without leaving a blind spot.

It was possible to advance towards the Zwinger between the two city walls without exposing oneself to the full mass of besiegers. This allowed early attackers who were said to have advanced this far to be pursued individually or in small groups. With this tactic, one could successfully resist even a numerically superior siege force.

Many towers of the outer line are so-called shell towers, i. that is to say, they are open at the back, so that the enemy could not take refuge once they crossed the first wall. Then it could still be attacked from the inner wall, for example by archers. However, the effectiveness of this defense has never really been proven.

In the 19th century, the already decaying city of Carcassonne was restored under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. This resulted in an extensive well-preserved historical monument that was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Carcassonne was founded as Carcasso in the 1st century BC. Founded by the Romans on the site of today's Cité. The so-called Gallo-Roman towers with a horseshoe plan on the inner wall testify to the Carcasso period.

On the 14 hectares, where between 3,000 and 4,000 people lived in the Middle Ages, 229 permanent residents live today. All the others work for tourism and live abroad. La Cité is a large open-air museum used by tourists and is not normally accessible by car.

Legend has it that the fortress was once besieged by Charlemagne, when Mme Carcas was the lady of the castle. The siege lasted so long that famine soon claimed the first victims in the Cité. Mrs. Carcas then decided to stuff a pig with wheat and, when she was fat enough, she threw it off the castle wall. The besiegers, already exhausted, thought when they saw the fat animal that fell from their towers that the city must have food to spare. Dejected, Charlemagne's men gave up and returned home. When the town bells rang to celebrate the end of the siege, one of the besiegers is said to have exclaimed Madame Carcas sonne (Carcas sounds).

In 1208, Pope Innocent III, faced with the increase and extension of Catharism, decreed the Albigensian Crusade. The Count of Tolosa and the Viscount of Carcassonne are accused of heresy and their territories become the main target of the attack by the barons from France. On August 1, 1209, the city is besieged by the Crusaders. Raymond Roger Trencavel surrenders to them on August 15 in exchange for the lives of its inhabitants. The villages around the city are destroyed. The viscount dies of dysentery in his castle prison on November 10, 1209. Other sources speak of an assassination planned by Simon de Montfort.

The city becomes the headquarters of the crusade troops. The land and city are delivered to Simón de Montfort, military chief of the Crusader army. He died in 1218 during the siege of Toulouse and his son, Amaury VI de Montfort, took possession of the city, but was unable to manage it. He cedes the rights to it to Louis VIII of France, but Ramon VII of Toulouse and the counts of Foix allied against the king. In 1224, Ramón Trencavel II took possession of the city after Amaury fled.

Louis VIII launches a second crusade in 1226 and Ramón Trencavel must flee. The city of Carcassonne becomes part of the domain of the King of France and becomes the seat of a seneschal. A period of terror is installed inside the city among the inhabitants; the search and hunting of the Cathars multiplies the bonfires in the squares and there are continuous savage denunciations, with the installation of an Inquisition Tribunal within the city precincts.

Louis IX of France orders the construction of the second walled enclosure so that the city can withstand long sieges and sieges. Trencavel, refugee in Aragon, intends to recover his land. At the same time, the king of Aragon, Jaime I the Conqueror, is considered a constant threat to the region, very close to the borders of his kingdom, the city being part of the defensive system of the border between France and Aragon.

After the annexation of Roussillon to France by the Treaty of the Pyrenees, the military role of Carcassonne was greatly reduced, as the distance to the Spanish border increased considerably. The role of command post for the defense of the border was transferred to Perpignan.

The walls of the Cité date from various periods of construction. The oldest parts of the wall were erected at the time of the Visigoths. They can be recognized by the layers of small cube-shaped stones, interrupted by layers of bricks, and by the narrowness of the towers, which are already equipped with real windows. The castle was mainly built in the 12th century. The outer ring of walls with their smooth ashlars dates from the middle of the 13th century.

At the end of the 13th century some of the towers and parts of the inner wall were built, which was then being rebuilt and advanced. The ashlars from this period are mostly carved with art. The towers have several floors and are provided with loopholes. The building material for the two concentric belts of fortifications was brought from the surrounding quarries: hard sandstone, difficult to extract and work, but which over the centuries began to erode under the influence of violent storms from the southwest.

The interior of the walls is made of rounded stones, fragments of rock and sand, agglutinated with lime, which also serves as mortar. The texture of the masonry varies with each period of construction.

The regular outer wall, 1.5 kilometers long, was built in 15 years shortly after 1230, hence its uniform appearance. The construction history of the 1.3 km long inner wall is much more complicated and its masonry is far from uniform. At that time, the city already had a wall from the Gallo-Roman era that was around 1,000 years old, but it was no longer up to date. Today it forms the skeleton of the inner belt and can often be seen at the bottom of today's wall.

As always in such cases, the area between the two walls is called the Zwinger. The kennel kept the attacker in an area that militia projectiles could reach. The wall must be as high as possible, because until the 14th century people did not shoot back, they shot back. In times of peace, such a kennel was used for games and knightly combat festivals. In some cases, the old parts of the wall were supported on new foundations when they were tapped, so that the strange picture arises that the oldest part is higher than the later one.

The ditch around the wall was not filled with water, but it had the function of preventing the use of larger siege engines, which had to be directed against the wall at right angles to the direction of the Zwinger and therefore did not have sufficient access. here. The fortification of the city with a double fence corresponded to a new defensive tactic that had been designed around 1200 around the king in the time of Philip Augustus (1180-1223). His principle was: the defense must be active, it must be able to inflict heavy losses on the attacker. Therefore, more than a thousand archers were stationed on the battlements, and the towers flanked the entire wall without leaving a blind spot.

It was possible to advance towards the Zwinger between the two city walls without exposing oneself to the full mass of besiegers. This allowed early attackers who were said to have advanced this far to be pursued individually or in small groups. With this tactic, one could successfully resist even a numerically superior siege force.

Many towers of the outer line are so-called shell towers, i. that is to say, they are open at the back, so that the enemy could not take refuge once they crossed the first wall. Then it could still be attacked from the inner wall, for example by archers. However, the effectiveness of this defense has never really been proven.