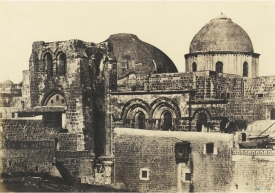

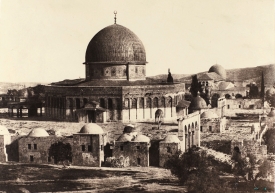

Jerusalem, a holy city for the three Abrahamic religions, underwent a profound transformation during the 19th century. After centuries of Ottoman rule, the city was caught up in a whirlwind of political, social and economic changes that redefined its urban landscape and demographic composition.

Jerusalem, a city where ancient echoes meet the footsteps of the modern world, stood at the crossroads of time during the 19th century. Amidst this period of profound transformation, the city was not only bridging its millennia-old traditions with modern influences but also experiencing significant turmoil. In 1834, during a peasant revolt that shook Palestine, Qasim al-Ahmad led his forces from Nablus, attacking Jerusalem with the help of the Abu Gosh clan. They entered the city on May 31, and the Christian and Jewish populations suffered various assaults. The following month, Qasim's forces were defeated by the Egyptian army of Ibrahim. Although Ottoman control was reestablished in 1840, many Egyptian Muslims remained in Jerusalem, and Jews from Algiers and other parts of North Africa began to settle in the city in increasing numbers.

During the 1840s and 1850s, the great international powers began a tug-of-war in Palestine seeking to increase the protection of religious minorities, a dispute carried out mainly by consular representatives in Jerusalem. According to the Prussian consul, the population in 1845 was 16,410, consisting of 7,120 Jews, 5,000 Muslims, 3,390 Christians, along with 800 Turkish soldiers and 100 Europeans. The number of Christian pilgrims grew under Ottoman control, and the city's population doubled by Easter. In the 1860s, new neighborhoods began to develop outside the walls of the Old City to accommodate pilgrims and to alleviate the severe overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions within the city. The Russian Compound and Mishkenot Sha'ananim were established in 1860; the latter was erected thanks to the donation of philanthropist Moses Montefiore, who financed the construction in the area of seven windmills—only two of which remain today—to encourage residents to move out of the walls and into the new neighborhoods. In the years and decades that followed, Mahane Israel (1868), Nahalat Shiv'a (1869), the German Colony (1872), Beit David (1873), Mea Shearim (1874), Shimon HaZadiq (1876), Beit Ya'aqov (1877), Abu Tor (1880s), the Swedish-American Colony (1882), Yemin Moshe (1891), and Mamilla and Wadi al-Joz were built around the end of the century. In 1867, an American missionary noted that the approximate population of Jerusalem was "above" 15,000 inhabitants, with between 4,000 and 5,000 Jews and 6,000 Muslims. Each year, between 5,000 and 6,000 Russian Christian pilgrims arrived. In 1874, Jerusalem became the center of a special administrative district called the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, independent from the Vilayet of Syria and under the direct authority of Istanbul.

Jerusalem in the 19th century was a crucible of change and continuity. As the Ottoman Empire tried to modernize, Jerusalem remained entrenched in its ancient traditions yet open to the influences shaping the broader world..

Historical and Political Context

In the 19th century, Jerusalem was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. This was a time of reforms (known as Tanzimat) aimed at modernizing the empire and improving administration. These reforms included the introduction of new legal and administrative systems, and in Palestine, the implementation of a census and the formalization of property titles. However, in Jerusalem, these reforms were unevenly felt, and the city remained primarily a religious and pilgrimage center.Jerusalem, a city where ancient echoes meet the footsteps of the modern world, stood at the crossroads of time during the 19th century. Amidst this period of profound transformation, the city was not only bridging its millennia-old traditions with modern influences but also experiencing significant turmoil. In 1834, during a peasant revolt that shook Palestine, Qasim al-Ahmad led his forces from Nablus, attacking Jerusalem with the help of the Abu Gosh clan. They entered the city on May 31, and the Christian and Jewish populations suffered various assaults. The following month, Qasim's forces were defeated by the Egyptian army of Ibrahim. Although Ottoman control was reestablished in 1840, many Egyptian Muslims remained in Jerusalem, and Jews from Algiers and other parts of North Africa began to settle in the city in increasing numbers.

During the 1840s and 1850s, the great international powers began a tug-of-war in Palestine seeking to increase the protection of religious minorities, a dispute carried out mainly by consular representatives in Jerusalem. According to the Prussian consul, the population in 1845 was 16,410, consisting of 7,120 Jews, 5,000 Muslims, 3,390 Christians, along with 800 Turkish soldiers and 100 Europeans. The number of Christian pilgrims grew under Ottoman control, and the city's population doubled by Easter. In the 1860s, new neighborhoods began to develop outside the walls of the Old City to accommodate pilgrims and to alleviate the severe overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions within the city. The Russian Compound and Mishkenot Sha'ananim were established in 1860; the latter was erected thanks to the donation of philanthropist Moses Montefiore, who financed the construction in the area of seven windmills—only two of which remain today—to encourage residents to move out of the walls and into the new neighborhoods. In the years and decades that followed, Mahane Israel (1868), Nahalat Shiv'a (1869), the German Colony (1872), Beit David (1873), Mea Shearim (1874), Shimon HaZadiq (1876), Beit Ya'aqov (1877), Abu Tor (1880s), the Swedish-American Colony (1882), Yemin Moshe (1891), and Mamilla and Wadi al-Joz were built around the end of the century. In 1867, an American missionary noted that the approximate population of Jerusalem was "above" 15,000 inhabitants, with between 4,000 and 5,000 Jews and 6,000 Muslims. Each year, between 5,000 and 6,000 Russian Christian pilgrims arrived. In 1874, Jerusalem became the center of a special administrative district called the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, independent from the Vilayet of Syria and under the direct authority of Istanbul.

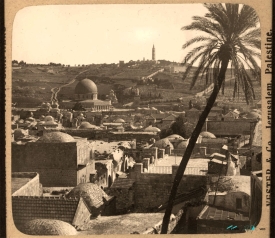

Archaeology and Rediscovery

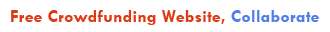

The 19th century was also a period of intense archaeological interest in Jerusalem. Explorers and archaeologists from Europe arrived hoping to uncover physical evidence that would corroborate biblical narratives. This focus not only increased knowledge about ancient Jerusalem but also reinforced the city's place in the global imagination.Jerusalem in the 19th century was a crucible of change and continuity. As the Ottoman Empire tried to modernize, Jerusalem remained entrenched in its ancient traditions yet open to the influences shaping the broader world..